home > Articles

ON FILM

- FROM INDIA TO AMERICA:

NEW DIRECTIONS IN INDIAN-AMERICAN FILM AND VIDEO

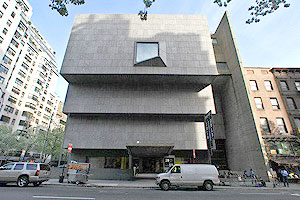

Exhibition Catalogue Essay, the Whitney Museum of American Art 1996

“From India To America: New Directions In Indian-American Film And Video” is the first exhibition of independent films and videos made by Indian Americans (1) as a body of work expressive of contemporary American culture. Many of the films and videos have been included in exhibitions and festivals of Asian American film and video, where they also rightfully belong, as well as in larger film festivals. Some, like Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay (1988) and Mississippi Masala (1992) and Ismail Merchant’s In Custody (1993), have been shown internationally and in theaters across the country. With “From India to America” we take a new perspective on Asian American media, independent film and video in the US, and on issues of immigration, bi-culturalism, inter-generational conflicts, assimilation/acculturation and identity. An additional perspective highlights intersections with current issues facing the entire country, such as feminism, labor, gender, and relations between the dominant culture and other minority groups.

“From India To America: New Directions In Indian-American Film And Video” is the first exhibition of independent films and videos made by Indian Americans (1) as a body of work expressive of contemporary American culture. Many of the films and videos have been included in exhibitions and festivals of Asian American film and video, where they also rightfully belong, as well as in larger film festivals. Some, like Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay (1988) and Mississippi Masala (1992) and Ismail Merchant’s In Custody (1993), have been shown internationally and in theaters across the country. With “From India to America” we take a new perspective on Asian American media, independent film and video in the US, and on issues of immigration, bi-culturalism, inter-generational conflicts, assimilation/acculturation and identity. An additional perspective highlights intersections with current issues facing the entire country, such as feminism, labor, gender, and relations between the dominant culture and other minority groups.

“From India to America” can be seen as a cross-section of independent American film and video. Where do these works fit in the socio-political and cultural landscape? For one thing, they employ the structural, formalistic and technological devices and strategies characteristic of independent film and video in the US. For another, they are expressive of the issues and themes of minority film and video, particularly part Asian American media. In doing so, they are part of the ongoing growing definition of independent as well as Asian American film and video.

It is generally agreed that Asian American media emerged with the Civil Rights and ethnic studies movements of the late 1960s. Until the early 1980s, there were only a few Asian American filmmakers with a body of work and most were college-educated Japanese or Chinese, predominantly male. Names that come to mind are Loni Ding, Art Nomura, Christine Choy, Taka Iimura, and Arnie Wong. Taking a broad framework posited by Renee Tajima, Asian American cinema shares some major characteristics. It is a socially committed cinema produced by a group defined by race and sharing interlocking cultural and historical relations, an experience of western domination, and characterized by diversity stemming from national origin and continuing waves of immigration. (2)

Indian American media shared most of these characteristics but with some important differences. Although Indian immigration to the US began around the mid-19th century, with the arrival of Indian farmers from the Punjab to the California coast, the population remained small, roughly at about 15,000 at the end of World War 2 (3). It was only after the 1965 Immigration Act that increasing numbers of white-collar immigrants from the Indian Subcontinent began to arrive in the US. But even as late as 1970, there were only about 75,000 Asian Indians in the US, out of a total Asian American population of about 1 million (4). A distinct Asian American culture such as emerging in the Chinatowns in major American cities did not evolve for the Indian American community. Given the demographics then, it is not surprising then that within the Asian American community, there was a marginalization of the small and incipient Indian American media of the 1960s and the 1970s.

The definition of Asia is to a great extent a historical and geographic convention arising out of a European worldview arising out of the industrial and mercantile expansion. The resulting incongruities were further complicated by the racial organization of American society, and its perception of different racial and ethnic groups. For Indian Americans from South Asia (and other groups especially from West Asia), the two factors of Asian American demographics and the racial structure of American society meant that most Americans did not see Indian Americans as Asians. Ironically, there was an “invisible minority” within the Asian American “visible minority”.

The twin factors of demographics and “invisibility” operating in tandem may account for the lack of political and social commitment in early Indian American works. There were very few Indian Americans working in the exciting new Asian American media centers like Visual Communications in Los Angeles and Asian CineVision in New York in the 1970s. The young leaders of the emerging Asian American media were usually second- or third- generation Asian Americans, who were responding with alternative strategies and means, using film to change the representation of Asians in American media and to document the history of Asian Americans in this country. They were also responding, having grown up in this country, to the racism in American society and countering the acute sense of disenfranchisement and using media as a tool for social change.

The input of Indian Americans in Asian American media was virtually non-existent at this stage. Early Indian American works tended to be about Indian culture or about non-Indian or non-Asian subjects altogether. It is not until the mid- and late 1980s, that a body of Indian American films expressing the agenda of social and cultural change can be seen.

In 1960, Ismail Merchant, a recent management graduate from New York University, produced a short dance film based on Indian mythology, and directed by Charles Schweep. The film was nominated for an Oscar and Merchant went on to the now well-known partnership that became Merchant Ivory Productions. In 1963, Amin Chaudhuri, a student at NYU’s film school directed and produced his first film, The Scandal that Rocked Britain, a black and white feature film in 35 mm based on the life of Christine Keeler, and starring Joanne McCarthy and Brooks Clift (the brother of Montgomery). The film was released theatrically and had a modest success. Chaudhuri went on to direct and produce between 1965 and 1968, three documentaries on Indian sculpture. There were few Indian-American films besides the ones produced by Merchant, who directed his first film The Mahatma and the Mad Boy in 1972, a short film made in India, and the films by Chaudhuri, which including a Living Camera episode with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (1969) for the television series produced by Richard Leacock and D. A. Pennebaker, until a new generation started making films in the post-Vietnam period. The subject matter still did not deal with Indian American life: Nair’s student film looked at the old city of Delhi in India and First Look (1982) by Kavery Dutta (now Kavery Kaul), documented the first visit by Cuban painters to the US, the first cultural exchange since Castro came to power.

It was only with Nair’s So Far From India (1982) that Indian Americans were first depicted on the screen. A film about an Indian newspaper vendor in the 116th Street and Broadway subway station in New York, and who works to send money back to his wife and family in India, it effectively portrayed the dual existence of an Indian American immigrant. Its very depiction of a world in America that had not been seen before on the screen was a political and social statement; but otherwise the film remained apolitical in its approach. It is important to note that these first Indian American filmmakers - Nair with Salaam Bombay and Mississippi Masala, Merchant with films directed by James Ivory and his own directorial efforts, Mahatma and the Mad Boy, Courtesans of Bombay (1983) and In Custody, Chaudhuri with several feature films including An Unremarkable Life (1990), and Kaul with her film on calypso music, One Hand Don’t Clap (1988) went on to make films that received mainstream acclaim and exhibition.

These films had limited visibility as Asian American or Indian American work. For one thing, these were all the Indian American filmmakers there were at the time, and so their successes did not emerge in the wake of a larger, established body of independent works by Indian Americans. For another, their “non-Indian” or “non-Asian” subject matter as in the case of Chaudhri and Kaul, or perhaps, ironically, the mainstream success and acceptance in the case of Merchant had the effect of their works being judged in terms of artistic and formal expression and not as a cinema of primarily documentary, sociological or historical interest, as often happens to minority artists. The result was by and large, a general unawareness of the existence Indian American filmmakers.

Since the mid-1980s there has been an increase in the number of works by Indian Americans, with a rise in immigrants from Asia following the relaxation of immigration in 1965, and the coming of age of first generation Indian Americans who either grew up or were born in the US. Attesting to the constant flux of people arriving in the US from Asia, many in this exhibition are works by immigrant or first-generation Indian Americans.

Starting in the mid-1980s, the independent sector produced Behroze Shroff’s Sweet Jail (1985) and Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam’s The New Puritans: The Sikhs of Yuba City (1986) both looking at the Indian farming community in California. What these early works did do was give face to an identity, and approach the issue of national origins and dual cultures. And that contributed to the on-going and changing depiction and expression of Asian American history and culture.

The world of the South Asian immigrant is approached in different ways. Sandeep Bhushan Ray’s Leaving Bakul Bagan (1993) follows in cinema verite style the last few days in the life of a young girl in Calcutta as she prepares to leave for college in the US. West is West (1988) David Rathod’s independent feature comedy is about a young man who arrives in San Francisco and finds himself on the run from the US immigration authorities. The supporting cast of West is West is telling of the immigrant experience: the Indian woman who runs the seedy hotel in the Tenderloin district, who alternately exploits and supports him, his immigrant buddy, and eventually the young American girl he falls with. Michelle Taghioff’s Home (1992) also following, in docu-drama form, another young girl, this time from Bombay, as she plans to leave for the US. But Home adds a further element, that of the filmmaker returning to Bombay, after years in the US, seeking to recapture a sense of belonging that she has never been able to find in her new home, and dealing with a powerful sense of loss and displacement.

Home, along with other works like Nair’s So Far from India, presents one sense of being and living in the US today. It is of people belonging to and living in two cultures but still inhabiting two worlds. In addition, taking these two films with a recent work like Taxi-Vala (1994) in which Vivek Renjen Bald, a young first- generation Indian American turns the camera to the world of the Indian taxi driver in New York and questions his relationship with one of the most visible groups of Indian Americans, one gets a nuance of the great class differences of Indian immigrants in this country. It is a difference that perpetuates the alienation of the Indian working class from the white-collar, college educated professional Indian American and it is a contradiction that cuts across other modes of immigrant identity in the US based on culture, race and language.

The need to find a place in the American social and racial organization and hierarchy emerges as another strong theme, as it does in many Asian American films and videos. Uprooted from a particular class and region in the home country, the immigrant must redefine himself in American terms. It is a long process, similar to but complicated by more pronounced ethnic differences and greater cultural distances from the earlier experiences of the immigrants from Europe. But as Indian American media really began to emerge in the 1980s in the Reagan-Bush era, these works reflect the sense of siege that many minorities felt. The works also show many different alliances around other issues such as women’s rights, gender politics, race and labor.

An overlapping of Indian American media with gender issues is seen in Hima B.’s Straight for the Money: Interviews with Queer Sex Workers (1994) - an expression of different modes of acculturation that come out even more strongly in films and videos relating to ethnicity and race and women’s issues. Kalliatt’s Jareena: Portrait of a Hijda (1990). about a young Indian transvestite provides an interesting flip-side to gender issues in India.

Sarin and Sonam’s The New Puritans: the Sikhs of Yuba City looked at the various stages of acculturation through work and marriage of a north Indian farming community in California. Even with advanced degrees of acculturation through education and socialization it becomes clear, in later work like Madhavi Rangachar and Maria T. Rodriguez’ (un)named (1992) and Erica Surat Andersen’s first-person account of her encounter with racial categorization in None of the Above (1993) that the construct of identity lies in constant negotiation. Andersen takes her camera and interviews of other children of mixed marriages, pointing to conflicts and differing expectations not only between the European American majority culture but between other minority groups such as African Americans and Asian Americans. The experiences are startlingly illustrative of the ways in which innocent but racially based perceptions continue to deny persons of color their personhood.

The theme of displacement of the Indian immigrant takes on additional perspectives in Indu Krishnan’s Knowing Her Place (1990). The camera turns a sympathetic lens on a first-generation Indian American woman married to an Indian immigrant and being confronted by the demands of a teaching career and her role as a traditional Indian housewife. Her relations with her teenager sons bring into sharp focus the additional strains within an inter-generational Asian family. This intersection of Asian, and in this instance Indian, immigration with other overarching issues of American society such as feminism, presents new avenues of thought. In Knowing Her Place, a fairly straightforward documentary and in Voices of the Morning (1992), Meena Nanji’s an experimental video, the urgency of women to seize control in defining their identity takes on an even more complex course as a patriarchal Asian Indian tradition joins forces with a male dominated American society. The objective discourse in Krishnan’s video, a verite reportage tempered with the artist’s intervention finds an obverse in the subjective voice in Nanji’s videotape. Even Nair’s India Cabaret (1986) and Children of Desired Sex: Boy or Girl? (1988), though shot and structured around an Indian frame of reference, derives from larger issues of feminism in contemporary American society.

Several works share the aesthetic of independent film and video in the US, as when the experimental video art of Ashraf Meer in Stages of Integrations (1990) and Ablutions (1992) and Nidhi Singh’s Fiji Shehnai (1990), incorporates the experiences of the Indian American artist or in the case of Hima B.’s Straight for the Money: Interviews with Queer Sex Workers, where Indian American identity takes a back seat to activist interventionist video.

Many of these artists, however, working in the mainstream or in alternative media, appropriate the cinematic form that is most distinctly Indian, that of the commercial Bombay film with its musical numbers. These range from direct clips as in the song sequence from Mr. India in Nair’s Mississippi Masala, followed by the singing of Hindi film songs at the wedding (featuring in a nice twist the Bombay film star Sharmila Tagore), to an interpretation of the use of music in film in Merchant’s In Custody, the party sequence in Rathod’s West is West or the use of a house music version of a popular Hindi film song in Taghioff’s Home. The irony is that the commercial Bombay cinema largely seen by the non-Westernized, vernacular Indian becomes the single most effective and visible mode of cinematic expression among Indians living in the West. The use of the commercial Indian film and film songs to provide a common social ground at diasporic gatherings of Indian Americans itself becomes a subject for the Indian American filmmaker as Sunita Chakravarty points out in the instance of Nair’s Mississippi Masala. (5)

“From India to America” represents a look at independent media, with roots in both the mainstream and alternative film, and the ways in which they have worked together to present America through Indian eyes and India refracted through the American experience.

L. SOMI ROY

Guest Curator

NOTES

(1) Indian Americans belong to the larger group identified in the US as South Asians, which largely includes people of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Sri Lankan descent.

(2) Renee Tajima: “Moving the Image: Asia American Independent Filmmaking 1970-90” in Moving the Image: Independent Asian Pacific American Media Arts

Edited by Russell Leong. UCLA Asian American Studies Center and Visual Communications, Southen California Asian American Studies Central, Inc. 1991

(3) The Harvard Encyclopedia of Ethnic Groups, Harvard University Press, 1980.

(4) Roger Daniels: “History of Indian Immigration to the United States: An Interpretive Essay” in Global Migration of Indians: Saga of Adventure, Enterprise, Identity and Integration. Edited by Jagat K. Motwani and Jyoti Barot-Motwani, National Federation of Indian-American Associations, 1989.

(5)National Identity in Indian Popular Cinema 1947-1987. Sumita S. Chakravarty. University of Texas Press 1993.

- FROM SOUTHWEST CHINA TO APPALACHIA

Read More

- FROM KENTUCKY TO KUNMING

Read More

- MANI KAUL AT FLAHERTY

Read More

Media

Buy Crimson Rainclouds Published

Buy Crimson Rainclouds Published

July 17, 2012

The English translation of M. K. Binodini's play "Asangba Nongjabi" by L.Somi Roy is now available on discount at NE-Bazaar.

Buy the Book »

re:PLAY 2012

re:PLAY 2012

Internesenal Film Kumhei

January 11-15, 2012

The second international film festival on performance and sports will be presented by the Manipur Film Development Corporation in Imphal, the capital of Manipur in North East India

Read More »

MLBI Coaching Camp

June 4 - 11, 2010

The third Major League Baseball International Coaching Camp will be held in Imphal, under the auspices of the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports and Hun-tré!, from June 4-11, 2010.